In this issue:

Writers Speak | Julie Moos on the writing and reading process

Interview | 4 Questions with Mark Kramer

Postcard from Paris — Pre-boarding

Tip of the week | Beware clichés of vision

Support Ukraine’s volunteer paramedics

Book World | Watch my YouTube interview about my book, 33 Ways Not to Screw Up Your Journalism

WRITERS SPEAK | JULIE MOOS ON THE WRITING VS. READING PROCESS

“Just because something is part of your writing process doesn’t mean it has to be part of my reading process.”

-Julie Moos

I remember distinctly when Julie Moos, my editor at Poynter Online, said this during an editing session. I was arguing for keeping something in a column. I was in love with it. But when she said those words about the writing and reading process, I understood for the first time that what a writer loves may not necessarily serve the needs of an editor — or a reader. I took out the section and ever since have tried to keep Julie’s wise counsel in mind.

INTERVIEW | 4 QUESTIONS WITH MARK KRAMER

Mark Kramer is a writer, professor and leader in the international movement to bring narrative journalism into books, magazines, documentaries, broadcasts, podcasts and news media. He teaches an independent master class for mid-career writers with longform projects. It explores the process from topic selection through to publication, and includes fieldwork, note-coding, structuring, drafting and revising, and covers sentence craft, voice, pace, scene-and-character portrayal and ethics.

Kramer started America’s leading narrative nonfiction writing conference at Boston University and continued it while writer-in-residence and founding director of the Nieman Program on Narrative Journalism at Harvard University, and then when it returned to Boston University. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Boston Globe and other papers, and in National Geographic, The Atlantic Monthly, Outside, Best American Essays, The Nation, etc.

His books include Three Farms: Making Milk, Meat and Money from the American Soil; Invasive Procedures: A Year in the World of Two Surgeons; and Travels With a Hungry Bear: A Journey to the Russian Heartland. He has co-edited two widely adopted textbooks: Literary Journalism; and Telling True Stories: A Writers’ Guide to Narrative Nonfiction from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University.

Kramer was writer-in-residence and professor of journalism at BU for a decade, and writer-in-residence at Smith College for a decade before that. He has also founded ongoing conferences in Amsterdam and Bergen, Norway, and shorter-lived conferences in Johannesburg, Lisbon, Rio and Paris. He’s finishing up a handbook for narrative journalists.

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer:

That we should be called “revisers” rather than “writers.” I spend perhaps 1 percent of my “writing time” writing, in new territory, filling blank pages. The rest is revising. And almost all the enduring “creative” stuff — the sentences and passages and juxtaposed scenes and ideas that still gleam when I reread them a few years later, happened while I was far into reworking text.

That said, writing that first draft, and even the scarily messy earliest revisions, are so awful compared with how good you want a piece to turn out, that we seem destined to cling to the illusion that we already know where we’re heading and the end is nigh. What’s more true is that a piece’s true destination, where you want readers to journey toward, looms up like a mirage at sea, as we persist in revising. And then when it does, we can really start pruning and shaping more exactly, and the destination and journey toward it will refine further.

Smoothing the phrasing is just one aspect of revising. When I strengthen and tune up sentences, I’m clearing the underbrush of half-formed, twice-said and superfluous words and ideas. That’s when the curve of the reader’s consecutive experience of the piece’s scenes and argument and sequence of realizations emerges, a hospitable trail you’re clearing through the woods. “Narrative arc” is a misleading term. It’s way too heavenly an aspiration for that practical period when you’re at your workbench knowing you ought to be constructing one. “Narrative arc” sounds expert but is bewilderingly hard to anticipate. How do you build a rainbow? You need one for a good piece, but you get there by considering what practical craft steps build a good scene, animate a lifelike character, tighten the next floppy sentence toward austerity. I find it helps me to ask myself repeatedly, “What should the reader experience next?” and then to work on that. If you think about how next to continue perfecting readers’ sense of “delightful and appropriate consecutiveness” in their reading experience, you’ll revise effectively. This is hard.

Solid structure is what the reader needs next, and in narrative work, it doesn’t spring from an outline. Revising develops it, if you favor improving the reader’s sequential flow of immersive scenes with good characters, pointing progressively toward aspects of the topic at hand (and, occasionally, feathering in interjected ideas). And of course, the reader’s experience also improves when you make the sentences you’ve drafted ever more simple, personable and elegant, until the reader is with you, a quiet, nearly invisible, host. “Curating the reader’s sequential experience” is an effective summary mission statement for the many chores of revising. And revising. And revising.

What should happen when the hospitably accompanied reader, after enjoying those efficiently purposeful scenes with their lifelike characters, arrives at that destination? Insight, as the elements of the narrative converge and finally drop the reader off there, is the reader’s reward. In high school and college English classes, I puzzled over the term “theme” that my teachers insisted writers had in mind, like the armature around which a sculptor forms clay. The puzzling term “theme” has misled many a talented writer to simplify a symphony into a monotone. Destinations of good work are nuanced. They preserve the humanness of situations intact, and don’t turn them into object lessons. And they succeed as the reader realizes things, not as the writer turns preachy and sums everything up.

First draft is merely shoveling up clay from a seam in the bed of a creek and slapping it down on the work table. Sculpting it after a first rough shaping, the work emerges, as they say, from removing what isn’t the sculpture until what’s left is, AND that’s mostly what writers do.

What has been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

The electrification stage of revision. Clearly, it takes patience bordering on endurance to report and research and sculpt your way through that first draft. Then comes the long revision period, revising the revision of your revision. You’ve immersed in your scenes, gone beyond what a deadline reporter might gain just from interviewing. You slowly, while drafting, comprehend the treasures hidden even from yourself in your field notes. Once you’ve nailed down and sharpened your selection and sequence of scenes, you’re getting there.

Then, something happens that rewards what may feel is fussy tinkering with every joint between every whole lot of words! That something is what I’ve come to think of as “the electrification stage” — it’s an analogy to when you frame and sheath and roof and sheetrock a house and the unfinished rooms are recognizable, in place. In your work, the scenes are mostly in place, the characters too, and that trail leading the reader from experience to experience still has a few extra loop-de-loops, but you finally know how it works. It’s a sequence from realization to realization maps in your mind. You suddenly know how to put it into place. It realizes in your mind. You suddenly can connect up the wiring you’ve installed in that house you’re building, and the lights go on. You’re not done yet. In fact, the illumination contains its own punishment — you can now see fussy little flaws and have to work far into the night, in the light you’ve created. And you can finally finish eliminating what you’d once thought essential but now you can see it’s superfluous, perhaps essential for your next piece, but not for this one. Voila: electrification draft.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer?

Please see above. I’ve got a sailor in the fog and a path-clearer on a hiking trail, a hospitable host, a carpenter building a house and briefly, a pilot doing those loop-de-loops. I guess I write to find out what I am, metaphorically.

What is the best writing advice anyone ever gave you?

Actually, it’s a pair of … advices. “!” and “fix.”

Those were the two marks that most often showed up in the drafts returned to me by my editor, friend and mentor, Dick Todd, late and much-missed editor at The Atlantic Monthly. He’d write a minuscule check in the margin when he really, really liked something a whole lot — an idea or little interstitial joke, or even a metaphor. He was given to eloquent understatement, but so brilliantly exacting that those scant checkmarks made me feel safe and enough on the right track so that when he occasionally also inscribed the word “fix” in the margins (also in tiny characters) I would realize some dumb misstep I’d made that would have remained invisible to me without his marks. The “!” showed me — in my late 20s, when I was just figuring things out — that the grace of an editor’s approving “!” was powerful in helping a writer feel safe enough to write on — or revise on. And I !!!’d a lot while working with other writers’ copy. And the “fix” showed me how fine-grained and precise is the sort of revision that a text needed before it felt like it made excellent contact with readers.

POSTCARD FROM PARIS — PRE-BOARDING

They burned the town hall in Bordeaux last night.

Normally, that news from the heart of wine country in France wouldn’t draw my attention. But in seven days I leave for an extended visit to Paris, where the City of Light and many others regions around the country, are gripped by strikes. At the heart of the conflict is President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to push through a law that changes the retirement age from 62 to 64. For Americans, who reach retirement age (when they are eligible to receive Social Security benefits) at 66 or 67 depending on when they were born, French retirement sounds sweet, but it’s an outlier. In Germany, the retirement age is 67.

But the French are wedded to this system, which is enshrined in the national culture. Macron’s move has prompted nationwide and, as in Bordeaux, sometimes violent protests.

Right now, a strike since March 6 by garbage collectors has left toppling, stinking sprawls of trash bags on Parisian streets, forcing pedestrians onto dangerous roads. The vaunted transit system is at times hobbled. Teachers have walked out of their classrooms.

All this should make for an illuminating experience for a tourist who happens to be a writer. I’ve decided to deliver postcards from the city and destinations elsewhere we plan to visit, via Chip’s Writing Lessons, to bring you to the front lines should the turmoil greet us there.

Of course, we’re hoping that it all blows over by the time we arrive at Charles de Gaulle International Airport on April 1. That the air is sweet and the sidewalks cleared and that furious protesters don’t clog the Place de la Concorde, a popular public square and tourist spot. With a long stay ahead, we plan to stray off the beaten path in ways that I hope will furnish indelible moments.

Why postcards? My interest dates back to July 2021 when Jacqui Banaszynski, my dear friend and editor at Nieman Storyboard, wrote a guest post in this space about what writing postcards can teach writers. With hopes that will be the case in France, whatever the situation on the ground, I leave you with Jacqui’s post:

WHAT POSTCARDS CAN TEACH WRITERS BY JACQUI BANASZYNSKI

Postcards have always held a special place in my life. If I were a collector, postcards would be high on my list. Not for the initial image, but for the act of sending and receiving, and the magic of storytelling involved in that action.

When I send students off into the world or reporters on assignment, the one thing I ask is that they send me a postcard. I’m always delighted when one follows through. I love seeing the images they choose, being introduced to their handwriting (a rare thing these days) and being enchanted by the mini-story they’ve chosen to tell me.

Because that’s another huge value of postcards. They are the perfect venue for practicing the craft — and purpose — of storytelling.

For years, when I traveled, I would send at least one postcard a day. I’d usually write at day’s end, perhaps at a bistro over a glass of wine, or maybe mid-afternoon over a coffee. My goal was not to say “Hey! I’m at the Parthenon!” But to instead share a moment or scene or experience from that day. To tell a story.

The ritual of putting pen to paper caused me to slow down and reflect on my day. To enter that mental/emotional story space that writers occupy.

Knowing I would write reminded me to report — to pay closer attention to the world as I moved through it. It caused me to be on alert to the little dramas that played out around me — to note the particular blue of the African dusk, the disorientation that came from staring at the stars in the southern hemisphere, how a table of Romanians kept guard over their too-drunk friend. (And yes, to find a post office and a stamp.)

Knowing the writing space was limited — maybe a 2- by 2-inch square — took the pressure off. The blank page/screen can seem endless and intimidating. A 2- by 2-inch postcard square? Hardly.

The reality of that space limit helped me focus. Verbs had to be active. Descriptions spare. Detours eliminated.

Writing on paper instead of the computer meant I had to accept my first draft and then let it go. No do-overs. (In daily news parlance, hit the SEND button!)

Knowing I would be writing to someone I cared about me made me care about what I wrote. It became an investment in a personal connection. I wanted them to see what I saw, to feel some of what I felt, to wonder a bit at my wonderment.

And that means I had to draw on the craft tools that writers employ to create story magic: scene, description, action, metaphor, dialog, sensory detail, tension, emotion.

All in a 2- by 2-inch square.

I carried this practice forward to classes and workshops. I once had students write a postcard a day for a month. Another time I had workshop writers pick someone they wanted to thank — maybe an inspiring teacher or the editor who gave them a chance or the brother who paid their rent one desperate month in college (Thank you, Jeff.) —and send that person a postcard. Capture their relationship and gratitude in a 2- by 2-inch square.

Of late I have transferred some of this practice to Facebook. When I’m overseas, I make it a mission to post a true story each day — what I think of as a nano-narrative. It still teaches me what, as writers, we all need to learn, relearn and practice:

Pay attention to the world around you. Slow down. Open yourself to experience. See with your eyes, your mind and your heart.

Find the center of a story. Develop a moment, a character, a scene, an experience.

Choose words that are vivid and precise, evocative and metaphorical.

Lower your standards and learn the value of Anne Lamott’s “Shitty First Draft.” Quit thinking at some point and write.

Write — deeply and personally — to someone you care about. Then learn to care about everyone who might read your writing.

Here are two of my nano-narratives from trips as evidence of all of the above. They are far from perfect. Just little stories.

Romanian Retrospective 14 (10.15.2012) Breakfast in Socodor, far western Transylvania. This was served the morning after a huge welcome dinner the night before. All made at Simina Mistreanu’s mother’s village farm or that of the neighbors. The tomatoes were picked that morning, served with the dew still on them and sweet as apples. Cheese and bread were delivered fresh by neighbors. Large plate of fat-back served with enthusiasm, but I said my health insurance would be cancelled if I indulged.

CHINA DISPATCH 9 (July 11, 2009) — I was prayed awake by chanting. Drifted over to the Daci Monastery next to the hotel, paid 3 yuan (45 cents) and entered an oasis of peace. Hundreds of women had shed shoes and purses, donned brown robes from a common laundry basket, and wound round and round the temple through a maze of prayer cushions, chanting in a low, meditative melody as an elderly monk rang a small brass bell to keep time.

TIP OF THE WEEK | BEWARE CLICHES OF VISION

Writers are well advised to avoid clichés of language, those worn-out phrases that lack originality and power. But there’s another type of cliché, stereotypes that are generalizations about a person or group of persons. Black people are inherent threats. All Asians are good at math. Bureaucrats are lazy. It’s lonely at the top. Clichés of vision are ways of looking at the world that, consciously or unconsciously, assume that certain stereotypes are correct.

Challenge those assumptions with rigor.

HELP UKRAINIAN PARAMEDICS SAVE LIVES

Royal Hospitallers, Ukraine's brave volunteer paramedic battalion, save lives every day in the war against Russia. Please support them here!

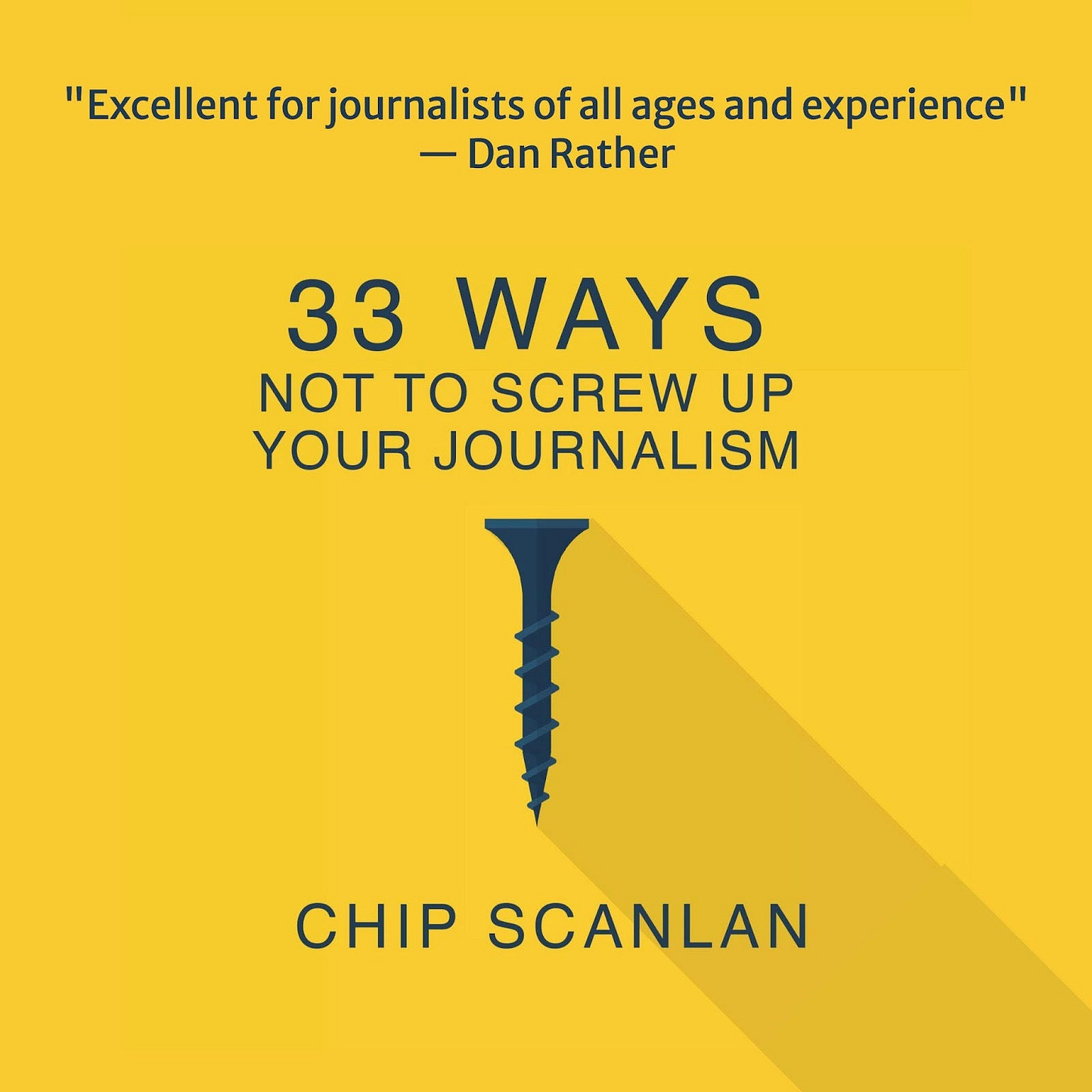

BOOK WORLD | MY YOUTUBE INTERVIEW ABOUT 33 WAYS NOT TO SCREW UP YOUR JOURNALISM

BEFORE YOU GO

If there’s one person you think would benefit from the interviews, craft lessons, writing tips, and more that appear every two weeks in my free newsletter, please suggest they subscribe, perhaps even become a paid subscriber. As you know, these members receive an extras package featuring excerpts from my books of writing advice, fresh interviews with leading writers and editors, inspirational quotes, coaching tips, my memoir-in-progress about my time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Africa, and more recommended readings and listening options.

MY BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE ON AMAZON AND TOMBOLO BOOKS, A LOCAL INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORE

33 Ways Not To Screw Up Your Journalism

Also available as an audiobook on Spotify and Amazon.

Writers on Writing: Inside the lives of 55 distinguished writers and editors “By asking four questions to 55 of our finest writers and editors, Chip Scanlan has hosted one of the greatest writing conferences you will ever attend." Roy Peter Clark, The Poynter Institute, “Writing Tools”

"A marvelous book for writers, people who have a passion for writing, or simply, who want to become writers. Yet what strikes me about this book is that it is not just for writers only." The Blogging Owl

Writers on Writing: The Journal

Available on Amazon and from Tombolo Books, a local independently-owned bookstore

chipscan@gmail.com | +1-727-366-8119

As always, thanks for reading and contributing. May your writing go well.